Source: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/jan/27/hungary-roma-living-in-fear

Families desperate to leave divided community after months of terror and years of segregation

Helen Pidd in Gyöngyöspata

guardian.co.uk, Friday 27 January 2012 16.04 GMT

The first snow of 2012 had fallen on the day Natasha Váradi invited us into the house she shares with her 10 children, mother and father-in-law in the Hungarian village of Gyöngyöspata. The two rooms were dark and dank: for four months the family had been living without electricity, gas or running water. Every half an hour a child went down the hill with a bucket to draw water from the communal pump. By night they stumbled around with torches as they squeezed on to mattresses.

The air in the bungalow carried the sour stench of urine. „They’ve started wetting the bed again,” said Natasha, who has lived in Gyöngyöspata for all of her 31 years. „Someone only need knock on the door and they are scared.” There is not much door left on which to knock. Much of the wood has been smashed in. On 22 December, the family say a stone came flying through the front room window.

The family members have reason to fear for their lives: seven adults and two children died in 49 attacks on Roma communities in Hungary between January 2008 and April 2011, according to the European Roma Rights Centre.

Until last Easter, 31-year-old Váradi had never left Gyöngyöspata, an old village 50 miles north-east of Budapest, which then had a population of about 2,800, including 450 Roma.

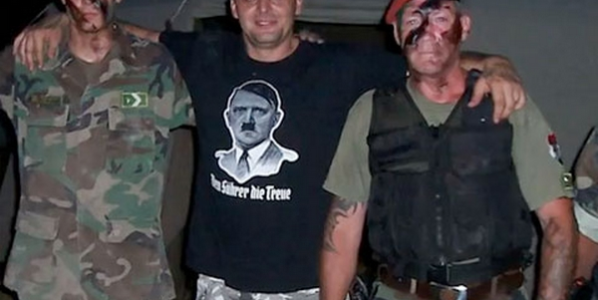

Then, on 1 March, the militia arrived. Wearing black uniforms and calling themselves the Civil Guard Association for a Better Future (Szebb Jövóért Polgárór Egyesület) they marched through the village singing war songs and bellowing abuse. Soon, they were joined by groups including Vederö (Defence Force), and the Betyársereg, wearing camouflage fatigues and armed with axes, whips and snarling bulldogs.

For almost two months they roamed the streets day and night, singing, hammering on doors and calling the inhabitants „dirty fucking Gypsies”. When they were not carrying out what they described as „neighbourhood watch patrols” designed to combat what they said were rising rates of „Gypsy crime”, the militia were drinking. CCTV cameras recorded one man drunk in the street, boasting at the top of his voice that he had just drawn a swastika in the dirt road with his urine.

The Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (HCLU) reported the four most serious incidents during the patrols to police. One involved a woman giving birth prematurely after being harassed by vigilantes with using racially abusive slogans. No charges have yet been brought against the militiamen, though a Roma man was jailed for two years after a fight with the vigilantes; a further five Roma are awaiting trial over the same incident.

Roma, who number somewhere between 400,000 and 800,000 in Hungary, are the prime targets for rightwing hate and more general discrimination. In March, Gábor Vona, the head of the far-right Jobbik party (which received 12% of the vote in 2010) gave a speech in Gyöngyöspata saying his party planned to start deploying similar „gendarmerie units” nationwide without delay.

In mid-April, a US businessman called Richard Field decided to act. The militia had announced plans to hold a „training camp” over the Easter weekend on the hillside overlooking the poorest part of the village, where most of the Roma live. Together with the Hungarian Red Cross, Field paid for six buses to evacuate the most vulnerable residents. On 22 April, shortly before 8am, 267 Roma women and children boarded the buses to spend Easter in one of two holiday retreats.

In the face of international outrage, the Hungarian interior minister called a press conference in which he denied that an emergency evacuation had taken place. The Roma were, he said, simply taking a „scheduled holiday”. In the event, the training camp never took place because police took eight extremists into custody, although no charges were brought.

By the end of the month, Field, who runs a private US charity called the American House Foundation, was under attack from the rightwing government. He was called to give evidence to a parliamentary „fact-finding committee”, which accused him of blackening Hungary’s name by tipping off the Associated Press about the evacuation or labelling it as such. The government maintained it knew about the Easter training camp and had always planned to deploy hundreds of police to the village that weekend.

Váradi and her children took one of Field’s buses to Szolnok and then stayed with relatives. On their return, most of the Defence Force had gone, but the fear remained. And all their utilities had been cut off.

For Váradi’s husband, it was all too much. By September he had scraped together enough money to fly to Canada, where he is trying to claim asylum.

Since Canada lifted visa restrictions for Hungarians in 2008, it has become a favourite destination for desperate Roma. Hungary was Canada’s top asylum claimant source country in 2010, with 2,297 cases referred to the Immigration and Refugee Board .

It appears that it will hold the top spot again in 2011, as figures for the first nine months of the year showed 2,545 Hungarian referrals, more than 1,000 above the second-highest source country, China. According to HCLU, 45 Roma children and 22 adults from Gyöngyöspata have left for Canada in the past six months. The Guardian asked Gyöngyöspata’s mayor, Oszkár Juhász, from the far-right Jobbik party, if he regretted or felt sad that the Roma feel they are being driven out of their own village. The village notary replied instead. „The Roma are not pushed out of their own village,” wrote Mátyás István. „Those who are not willing to work here will not work in other places either.”

The Hungarian minister for government communication, Zoltán Kovács, in response to the same question, said: „We regret that some are utilising the situation and that some Roma people are leaving the country on an argument that is not valid.” In a phone interview he suggested the Hungarian Roma who claim asylum in Canada plea persecution in order to „make money” and milk the benefit system. „We don’t think there is any foundation for [Hungarian Roma to claim asylum because they are being persecuted for their ethnicity],” he said, adding: „We want every Hungarian citizen to stay here.”

Nonetheless, Váradi said she and her children – who range in age from two to 16 – were going to Toronto as soon as they had the air fare. „We have no life here any more,” she said. Asked what she hoped for in Canada, Váradi did not speak of material gain. „My husband says it’s good there. He says there is going to be happiness, that people there will offer us love.”

When the Guardian mentioned Natasha’s case to the local council, asking what they were doing to help the poorest members of the community, the notary asked us a question instead of answering ours. „The head of that household is in Canada, alone. What is your opinion on this?” He said the family had only recently asked the council for help. „If we can, we will help them,” he insisted.

It can be hard to understand how such a situation can unfold in the EU. But talk to locals, Roma and non-Roma, and it is clear that segregation is at the very heart of the community.

Both sides agree that until last March, the two groups coexisted relatively peacefully. There were „small incidents” with Roma accused of pilfering firewood or vegetables and other petty crime, but only 12 „petty larcenies” were reported to police during the first four months of 2011. Violence was rare. But the youngest members of the community quickly learned that not all children are equal in Gyöngyöspata.

The primary school is run on a sort of apartheid system, say lawyers who have brought a lawsuit against the local authority on behalf of the charity Chance for Children Foundation. Their report claims: „Romani children are illegally separated from non-Roma in separate classes, which are also physically separated from each other (Roma classes are on the ground floor, non-Roma are on the upper floors). This separation involves school separation of Roma and non-Roma children in the restrooms, school festivities and school lunch.”

When the Guardian visited the school, we saw a marked difference between the quality and condition of equipment on the two floors. The classrooms on the upper levels had electronic whiteboards; downstairs, where the Roma are taught, they make do with a blackboard. Roma children we spoke to complain that only „upstairs” children receive swimming lessons, and that they are not allowed to use computers in class until several years after the non-Roma. They are excluded from after-school activities and are not allowed to use the superior toilet facilities on the first floor.

The Gyöngyöspata authorities deny the allegations and the case is ongoing. The school did not respond to our request for comment.

When asked what the government was doing to help the Roma in Gyöngyöspata and beyond, Kovács said it did not see the problems as being ethnically based, adding: „We are aware that some problems the Roma are facing are problems because they are Roma, but in general terms, these are social, educational and labour market problems.” His government, he said, was rejuvenating the job market by getting people off benefits and into work: „Everyone should work who can.” It was the „saddest figure in Europe„, he said, that Hungary had the lowest employment rate in the EU.

For the long-term unemployed – a disproportionate number of whom are Roma – this means taking part in the government’s new public work programme. According to Jeno Setét, a Roma activist, between 70% and 80% of Hungary’s Roma population do not work (the rate for the whole population is around 10%). This scheme aims to get 300,000 people into work by 2014 via a sort of community service scheme for which participants are paid less than the national monthly minimum wage (around 80,000 HUF – £214 – for unskilled workers) but slightly more than they would receive in benefits.

Anyone unemployed for 90 days is offered a place on the programme, which administers projects cleaning streets or sewers, cutting down trees or building football stadiums or dams. Refusal to accept a placement will result in all social security benefits being stopped to the refusenik and family. Gyöngyöspata was chosen last year to run a pilot scheme. Unemployed locals – almost exclusively Roma – were deployed to cut down trees in a nearby wood.

For Setét, the public work scheme is a „smokescreen” that will do little to help Roma get „real” jobs and will reinforce their position at the bottom of Hungarian society. „If people on the scheme were paid properly and trained properly, I’d be all for it,” he added. „But they are not. Right now it’s a way of humiliating people and paying them a slave wage.”

The most controversial aspect of the programme is the introduction of what Roma activists call „labour camps”. If there is no suitable project near enough for someone to commute to, they will be offered „accommodation” near or on site, said Kovács. „They are not labour camps,” he said. But to the Hungarian Roma, many of whose relatives perished the last time they were sent off to „labour camps”, during the Nazi era, the merest whiff of anything similar is spine-chilling, said Gábor Sárközi from the Roma Press Centre: „People are absolutely terrified at the prospect.”

2012. január 28. szombat, 13:57 → Dalit.hu

0